Python is by design a dynamically typed programming language. It is flexible and easy to write. But as the project size grows, there will be more interactions between functions, classes and modules, and we often make mistakes like passing wrong types of arguments or assuming different return types from function calls. Worse still, these mistakes can only be spotted at runtime, and are likely to cause production bugs. Is it possible for Python to support static typing like Java and Go, checking errors at compile time, while remaining to be easy to use? Fortunately, from Python 3.5 on, it supports an optional syntax, or type hints, for static type check, and many tools are built around this feature. This article covers the following topics:

- A quick start to do static type check in Python.

- Why do we need static typing?

- Python type hints in detail.

- Other advanced features.

Quick start

Static typing can be achieved by adding type hints to function arguments and return value, while using a tool like mypy to do the check. For instance:

1 | def greeting(name: str) -> str: |

Here the function greeting accepts an argument which is typed as str, and its return value is also typed str. Run pip install mypy, and then check the file:

1 | % mypy quickstart.py |

Clearly this simple function would pass the check. Let’s add some erroneous code:

1 | def greeting(name: str) -> str: |

There will be plenty of errors found by mypy:

1 | % mypy quickstart.py |

The error messages are pretty clear. Usually we use pre-commit hook and CI to ensure everything checked into Git or merged into master passes mypy.

Type hints can also be applied to local variables. But most of the time, mypy is able to infer the type from the value.

1 | def greeting(name: str) -> str: |

real_name would be inferred as str type, so when it is assigned to number, an int typed variable, error occurs. The return value also includes an error.

1 | % mypy quickstart.py |

There are basic types like str, int, and collection types like list, dict. We can even define the type of their elements:

1 | items: list = 0 |

You may see some code written as List[int] or Dict[str, int], where List is imported from the typing module. This is because before Python 3.9, list and other builtins do not support subscripting []. This article’s examples are based on Python 3.10.

1 | % mypy quickstart.py |

The check works as expected: items is a list, so it cannot be assigned otherwise; nums is a list of numbers, no string is allowed; the value of ages is also restricted. Look carefully at the first error message, we can see list is equivalent to list[Any], where Any is also defined in typing module, which means literally any type. For instance, if a function argument is not given a type hint, it is defined as Any and can accept any type of value.

Please remember, these checks do not happen at runtime. Python remains to be a dynamically typed language. If you need runtime validation, extra tools are required. We will discuss it in a later section.

The last example is defining types for class members:

1 | class Job: |

Type hints could be applied either in class body or in constructor. Member functions are typed as normal.

1 | % mypy quickstart.py |

Why do we need static typing?

From the code above we can see that it does take some effort to write Python with type hints, so why is it preferable anyway? Actually the merits can be drawn from many other statically typed languages like Go and Java:

- Errors can be found at compile time, or even earlier if you are coding in an IDE.

- Studies show that TypeScript or Flow can reduce the number of bugs by 15%.

- Static typing can improve the readability and maintainability of the program.

- Type hints may have a positive impact on performance.

Before we dive into details, let’s differentiate between strong/weak typing and static/dynamic typing.

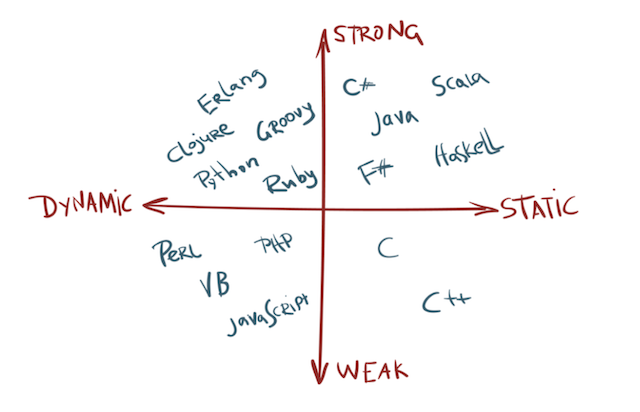

Static/dynamic typing is easier to tell apart. Static typing validates variable types at compile time, such as Go, Java and C, while dynamic typing checks at runtime, like Python, JavaScript and PHP. Strong/weak typing, on the other hand, depends on the extent of implicit conversion. For instance, JavaScript is the least weakly typed language because all types of values can be added to each other. It is the language interpreter that does the implicit conversion, so that number can be added to array, string to object, etc. PHP is another example of weakly typed language, in that string can be added to number, but a warning will be reported. Python, on the contrary, is strongly typed because this operation will immediately raise a TypeError.

Back to the advantages of static typing. For Python, type hints can improve the readability of code. The following snippet defines the function arguments with explicit types, so that the checker would instantly warn you about a wrong call. Besides, type hints are also used by editor to provide informative and accurate autocomplete for invoking methods on an object. Python standard library is fully augmented with type hints, so you can input some_str. and choose from a list of methods of str object.

1 | from typing import Any, Optional, NewType |

For some languages, type hints also boost the performance. Take Clojure for an example:

1 | (defn len [x] |

The untyped version of len costs about ten times longer. Because Clojure is designed as a dynamically typed language too, and uses reflection to determine the type of variable. This process is rather slow, so type hint works well in performance critical scenarios. But this is not true for Python, because type hints are completely ignored at runtime.

Some other languages also start to adopt static typing. TypeScript, a superset of JavaScript with syntax for types:

1 | const isDone: boolean = false |

And the Hack programming language, which is PHP with static typing and a lot of new features:

1 | hh |

That being said, whether to adopt static typing for Python depends on the size of your project, or how formal it is. Luckily Python provides a gradual way of adopting static typing, so you do not need to add all type hints in one go. This approach will be discussed in the next section.

Python static typing in details

PEP

Every new feature in Python comes with a PEP. The PEPs related to static typing can be found in this link. Some of the important ones are:

- PEP 3107 Function Annotation (Python 3.0)

- PEP 484 Type Hints (Python 3.5)

- PEP 526 Syntax for Variable Annotations (Python 3.6)

- PEP 563 Postponed Evaluation of Annotations (Python 3.7)

- PEP 589 TypedDict (Python 3.8)

- PEP 585 Type Hinting Generics In Standard Collections (Python 3.9)

- PEP 604 Allow writing union types as X | Y (Python 3.10)

Python 3.0 introduces the annotation syntax for function arguments and return value, but it was not solely designed for type checking. From Python 3.5, a complete syntax for static typing is defined, typing module is added, and mypy is made the reference implementation for type checking. In later versions, more features are added like protocols, literal types, new callable syntax, etc., making static typing more powerful and delightful to use.

Gradual typing

One thing that never changes is that static typing is an opt-in, meaning you can apply it to the whole project or only some of the modules. As a result, you can progressively add type hints to certain parts of the program, even just a single function. Because in the default setting, mypy will only check functions that have at least one type hint in its signature:

1 | # Check |

For untyped argument, like name in the first greeting, it is considered as Any type, which means you can pass any value as name, and use it for any operations. It is different from object type though. Say you define an argument as item: object and try to invoke item.foo(), mypy will complain that object has no attribute foo. So if you are not sure what type of a variable is, give it Any or simply leave it blank.

1 | # Check |

Another common mistake is for functions without arguments and return value. We have to add None as the return type, otherwise mypy will silently skip it.

Type hints

There are two ways to compose type hints: annotation and stub file.

1 | # Annotation |

... or Ellipsis is a valid Python expression, and a conventional way to leave out implementation. Stub files are used to add type hints to an existing codebase without changing its source. For instance, Python standard library is fully typed with stub files, hosted in a repository called typeshed. There are other third-party libraries in this repo too, and they are all released as separate packages in PyPI, prefixed with types-, like types-requests. They need to be installed explicitly, otherwise mypy would complain that it cannot find type definitions for these libraries. Fortunately, a lot of popular libraries have embraced static typing and do not require external stub files.

Mypy provides a nice cheat sheet for basic usage of type hints, and Python documentation contains the full description. Here are the entries that I find most helpful:

1 | # Basic types |

One of my favorite types is Optional, since it solves the problem of None. Mypy will raise an error if you fail to guard against a nullable variable. if x is not None is also a way of type narrowing, meaning mypy will consider x as str in the if block. Another useful type narrowing technique is isinstance.

Python classes are also types. Mypy understands inheritance, and class types can be used in collections, too.

1 | class Animal: |

Type alias is useful for shortening the type definition. And notice the quotes around Dog. It is called forward reference, that allows you to refer to a type that has not yet been fully defined. In a future version, possibly Python 3.12, the quotes may be omitted.

Another useful utility from typing module is TypedDict. dict is a frequently used data structure in Python, so it would be nice to explicitly define the fields and types in it.

1 | from typing import TypedDict |

TypedDict is like a regular dict at runtime, only the type checker would see the difference. Another option is to use Python dataclass to define DTO (Data Transfer Object). Mypy has full support for it, too.

Advanced features

Generics

list is a generic class, and the str in list[str] is called a type parameter. So generics are useful when the class is a kind of container, and does not care about the type of elements it contains. We can easily write a generic class on our own. Say we want to wrap a variable of arbitrary type and log a message when its value is changed.

1 | from typing import TypeVar, Generic |

We can define functions that deal with generic classes. For instance, to return the first element of any sequence-like data structure:

1 | from typing import TypeVar |

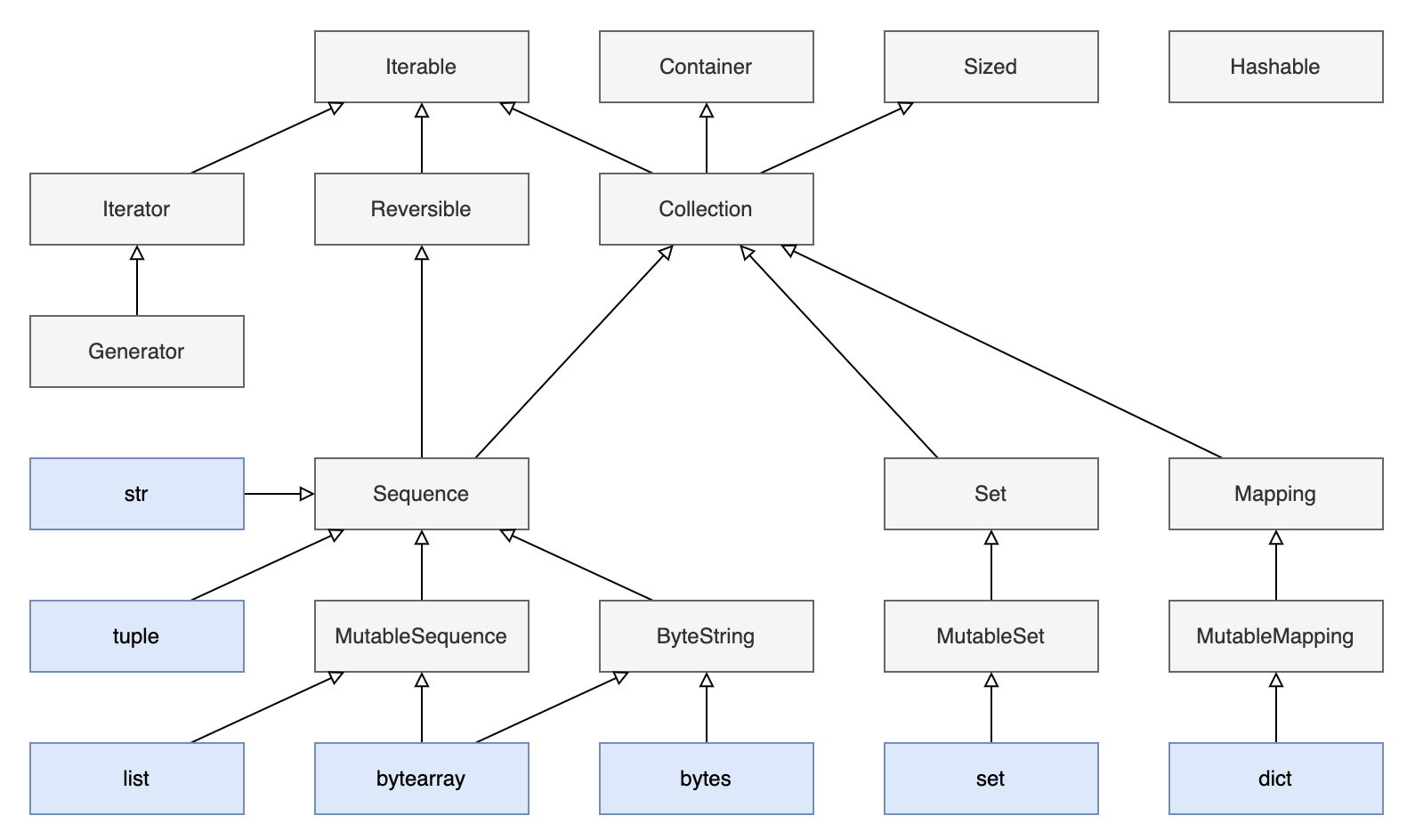

Sequence is an abstract base class, which we will discuss in the next section. list and str are both subclasses of Sequence, so they can be accepted by the function first.

Type parameter can also have a bound, meaning it must be a subclass of a particular type:

1 | from typing import TypeVar |

list, set, and str are all subclasses of Sized, in that they all have a __len__ method, so they can be passed to longer and len without problem.

Abstract base class

Sequence and Sized are both abstract base classes, or ABC. As the name indicates, the class contains abstract methods and is supposed to be inherited from. There are plenty of predefined collection ABCs in collections.abc module, and they form a hierarchy of collection types in Python:

Mypy understands ABC, so it is a good practice to declare function arguments with a more general type like Iterable[int], so that both list[int] and set[int] are acceptable. To write a custom class that behaves like Iterable, subclass it and provide the required methods.

1 | from collections.abc import Sized, Iterable, Iterator |

Duck typing

In the previous code listing, what if I remove the base class:

1 | class Bucket: |

Is the class instance still assignable to Iterable[int]? The answer is yes, because Bucket class would behave like an Iterable[int], in that it contains a method __iter__ and its return value is of correct type. It is called duck typing: If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck. Duck typing only works for simple ABCs, like Iterable, Collection. In Python, there is a dedicated name for this feature, Protocol. Simply put, if the class defines required methods, mypy would consider it as the corresponding type.

1 | # Sized |

It is also possible to define your own Protocol:

1 | from typing import Protocol |

Runtime validation

Type hints are mostly used in static type check, and do not work at runtime. To check variable types at runtime, we can either write code on our own, i.e. isinstance, or use third-party libraries. Two popular choices are typeguard:

1 | from typeguard import typechecked |

And pydantic:

1 | from pydantic import BaseModel |